For more than 25,000 years, the southern ACT catchment area has been the home of the Ngunawal people. Their country stretches from Queanbeyan and Yass to Wagga Wagga, where it borders the Wiradjuri people's lands. Other groups such as Walgalu, Gundungurra, Yuin, and Ngarigo peoples are known to have been active in the region.

The Ngunawal people left their mark on the southern ACT catchment, with various artefacts such as axe-grinding grooves, campsites, rock shelters, paintings, stone artefact scatters, ring trees, and scar trees, some of which date back to the last Ice Age. Radiocarbon dating from the Birrigai Rock Shelter near Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve places Ngunawal occupation at least 25,000 years ago. However, Aboriginal people believe their ancestors were here well before this time.

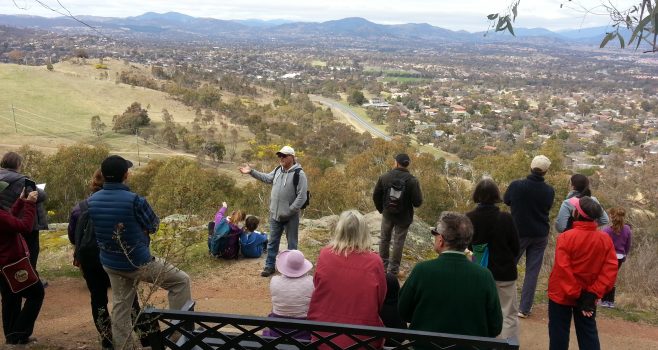

The Aboriginal communities in the area travelled according to seasons to find food and shelter. In the warmer seasons, many people gathered in the Tuggeranong Valley to harvest Bogong moths that arrived in abundance annually in the Brindabella ranges - which they roasted in sand or ashes. This gathering provided an opportunity for the tribes to come together for important occasions such as initiation ceremonies, marriages, ceremonial dancing, food exchange, and dispute resolution. The cultural traditions and connections with the land were passed down from generation to generation during these gatherings.

When European settlers arrived in canberra in the early 1820s, there were still a large number of Ngunawal people living in the area. But within two decades, European settlement began to disrupt Aboriginal patterns of land use and movement across the country. Many Aboriginal families were drawn to farms and townships by the opportunity to work or to receive food and blankets. As contact with Europeans increased, many Aboriginal people died from diseases like influenza, smallpox, and tuberculosis, and soon Aboriginal populations began to decline.

Today, the Ngunawal community is active in restoring their connections to their dispossessed custodial lands and cultural heritage. In 2001, the ACT government entered into a cooperative agreement with the Ngunawal community over the management of the ACT's Namadgi National Park. This agreement recognised the Ngunawal cultural association with the park's lands and their role as custodians of their traditional lands and responsibilities to their ancestors and descendants for the protection of their sites.

The Theodore Aboriginal artefact grinding grooves demonstrate an important aspect of past Aboriginal lifestyles and technologies. The site has exposed sandstone rock with grooves and scattered stone artefacts. There are two shapes of grooves here at Theodore. The round grooves were used for food processing and the oval-shaped for making and sharpening tools. Southern ACT Catchment Group worked with Ngunawal elder Wally Bell to install an educational sign at the site to allow for the canberra community to learn and appreciate ancient cultural heritage.